Placement, orientation, lineage affiliation

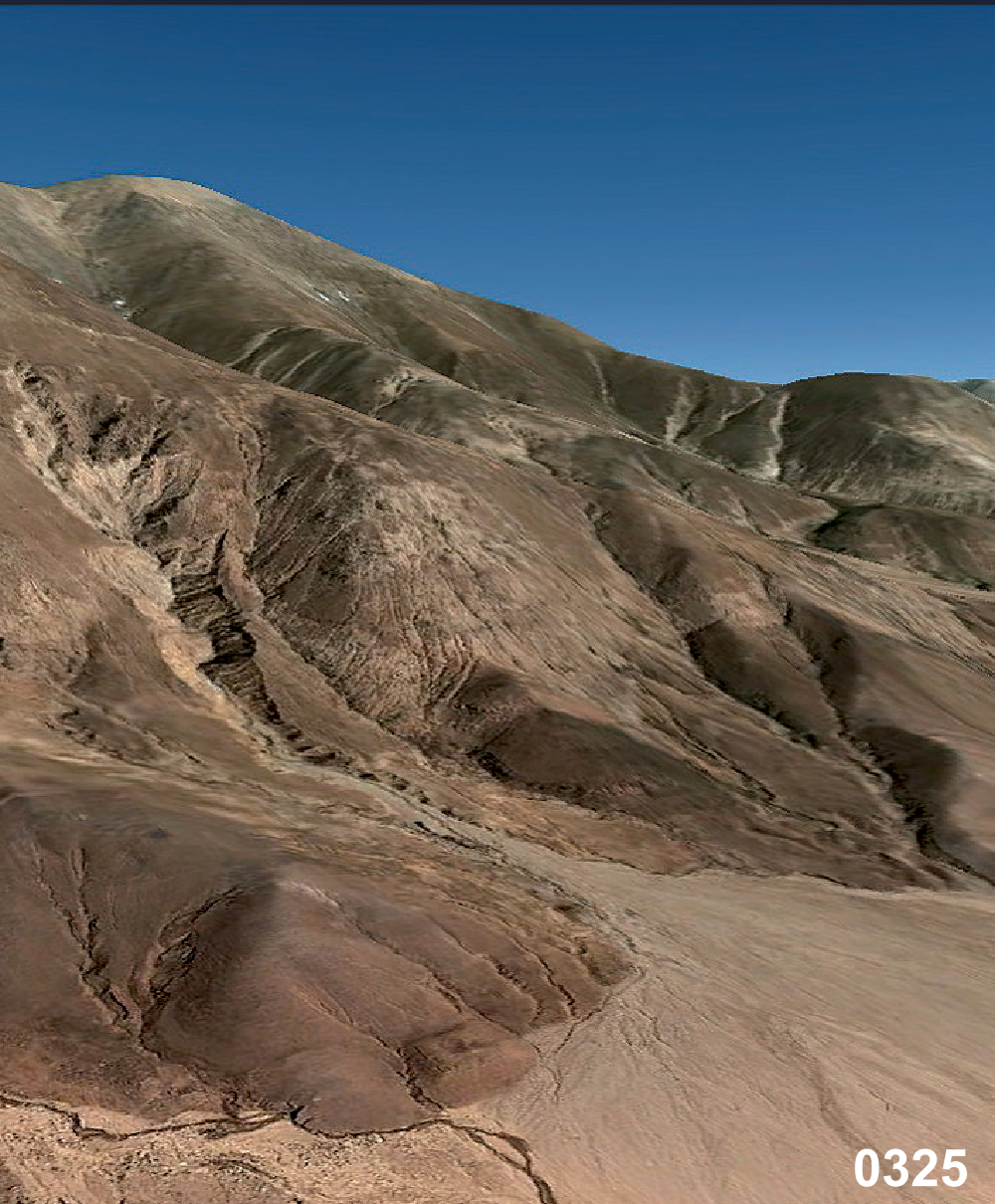

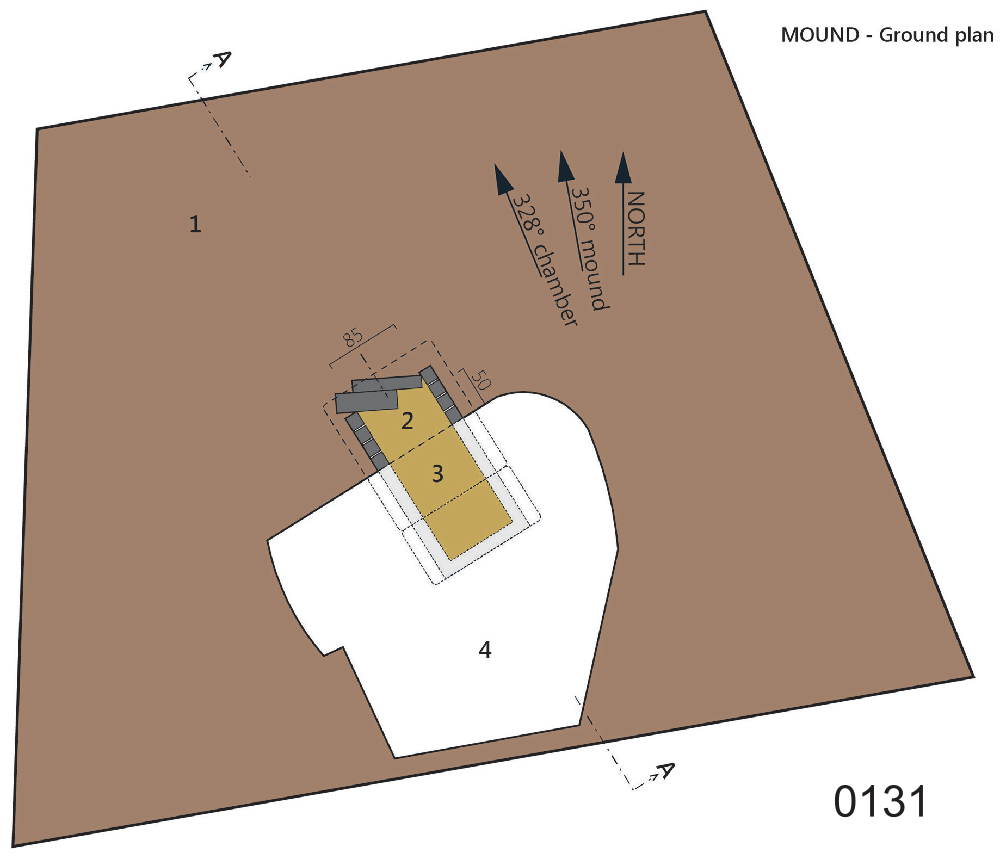

One clear criterion for the choice of location of a grave field or group of tombs is to be found in the fact that the agriculturally non-usable zone was preferred (see Plate “field type”), and also a certain proximity to the native place of the families for which the cemetery was established can be assumed. Thus it is easily conceivable, for example, that the establishment of the field #0003 above the village G.yu gsar in Lower Yarlung (see sat-map above) started with the tomb M-1 erected for a noble and representative of the state, who may well have been a native of this village (or its forerunner settlement), and whose lineage relatives were later buried around his resting place. Often there are several cemeteries in close proximity to each other, each with greater elite tombs, which suggests the existence of different noble families in one and the same settlement area and also points to the issue of chronology in the establishment of grave fields, for instance when larger chambered tombs (which are to be dated to the imperial period) are separated from fields with smaller, and much more eroded and thus probably older (pre-imperial) graves. A particular issue is the position of graves in their spatial relation to each other. The bird-shaped field #0024 in ’On constisting of 18 structures (see Site “#0024”) possibly indicates certain kinship relations of the persons buried there, where, however, the examination on site suggests to identify the 10 structures behind the main mound rather as the remains of sacrificial pits (Hazod, “Territory, kinship and the grave”, in-press). Other particularities concern “twin (or triplet-) tombs”, where two or more structures merge into one building, perhaps indicating the burial of a high lineage represesentative and his wife (wives) (above #0112; Hazod, in press-a). The majority of burial sites have a certain scenic unobtrusiveness. This applies in particular to the trapezoidal strucures that as it were merge with the mountain landscape, and in fact appear to have been designed to conform with the shape of the mountain slope, with the longer front facing the valley floor and river (cf. #0325 above). In fact the characteristic trapezoidal shape seem to follow no orientation pattern other than the direction towards the valley floor. Often we find cemeteries located on the opposite side of the valley (see above the example of Lower Yarlung), a situation which evidently excludes a common orientation – related to the sky or also specific landscape markers such as a mountain as the seat of the representative territorial god. This is also evident by the characteristic deviation of the grave’s direction within one and the same field: in a cemetery of dozen of adjacent trapezoidal mounds we see at almost any grave an individual direction (above #0112). Yet it is clear that the orientation of the outer (trapezoidal) structure represents only one reference point, which must be distinguished from the orientation of the grave chambers and the position of the coffin or corpse. Recent on site surveys at opened mounds reveal a clear deviation of the alignment of the main chamber from the outer trapezium (see the example of #0131) – a situation which together with other indications allow us to assume the concept of a heavenly orientation behind the practice of interment, one that was combined with astronomical calculations. (See Hazod 2016 for a first clarification of this issue.)